50 years ago, a day like today, the first brick was put in place to begin building a wall in the west. Those bricks, that wall, divided families, friends and a culture. That wall created a fictitious division among human beings, it became a symbol of intolerance installed by hidden interests of a government, a wall that didn’t reflect who the people were but presumed to be the spirit of the people. Year after year those bricks, that wall, created a wall in the mind of the people, and imposed a man-made separation that was normalized by its mere presence.

We have other walls today, walls constructed around us, artificial and invisible walls that separate people, that affect human lives. Those invisible walls make us forget the only search and the only lesson that survived all generations, all cultures, all religions: the satisfaction of being a better human being.

But how can we be a better human being if we know and we see injustice yet continue under a falsely normalized reality, where we pretend that justice and law are the same thing.

For how many years was human trafficking and slavery a normalized practice? People back then thought it was normal; it was perfectly justified, they were even excited about it, now we would be horrified, now we persecute human trafficking because we know that no human being can be treated like a product, that every human being has human rights that we need to respect.

For how many years were people separated because the color of their skin, even not allowed to enter certain places? Now, we would not even understand how that could have happened, we were all united against South African apartheid, we are all ready to unite against any other form of racial discrimination.

For how many years were women just a reproduction accessory and marginalized to home labor? And now the chancellor of Germany is a woman.

For how many years was education the right of the wealthy? Now education is a human right, even if some people have to be reminded of it.

For how long are we going to let a dress done by the maquiladoras in México travel freely and with rights while a Mexican is not permitted to travel freely and with their human rights. For how long we will enjoy a kebab while a Turkish is not permitted to travel freely and with their human rights. For how long will objects, products and ideas be considered by governments and companies part of globalization, while immigrants are seen as a local or a national issue.

It is not hard to imagine, in a few years, our kids trying to understand whyimmigrants were treated as they are treated today; trying to understand even, why there were people called immigrants; the same way we don’t understand today how slavery lasted for so long.

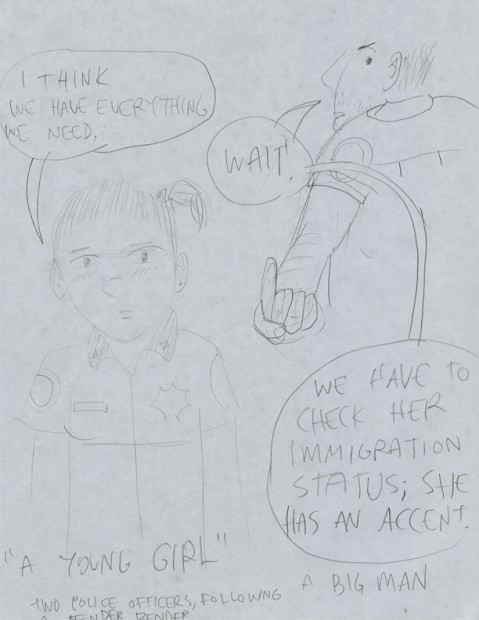

There are too many examples of injustices justified by the law to let them keep happening. The law is made by mankind and it is men who create artificial separations that lead into real suffering. The latest of those constructed and unnecessary separation are immigrants. What I do not understand is the efforts to demonize immigrants.

Anders Breivik, the Norwegian extremist, killer and confessed perpetrator of dual terrorist attacks in Norway last 22 July: bombing government buildings in Oslo that resulted in eight deaths, and the mass shooting at a camp of the Workers’ Youth League (AUF) of the Labour Party on the island of Utøya where he killed 69 people, he is not an immigrant and immigrants are not demonizing him.

The list of people committing crimes against humanity who are not immigrants is extremely long and that doesn’t make immigrants see everybody else as a criminal. Immigrants will never demonize these people, because if immigrants understand something it is that people are different and you can not judge them as a group, you can not judge them for the color of the skin, you can not judge them from where they come from, you can not judge them for their money, nor even for the political party they are affiliated to, you can only judge people for their actions.

I can’t understand the efforts to make immigrants a homogeneous group ignoring the richness of their origins, their reason to migrate, their experiences and skills.

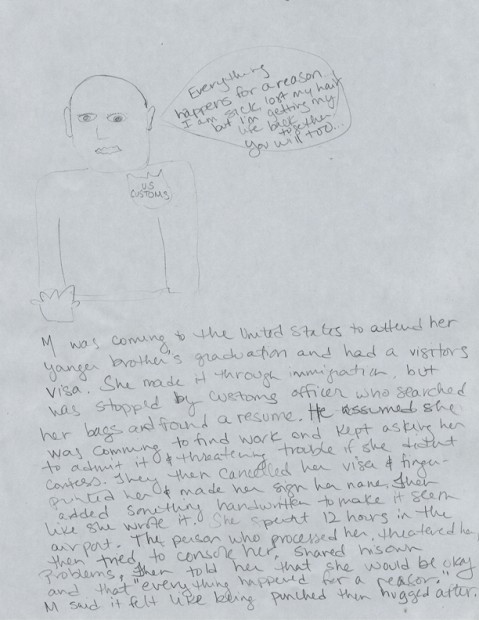

I’m an immigrant myself and I have gone to the harsh process to incorporate on a new society, one very different from where I came from. I remember when I didn’t want to be integrated in that new society, I didn’t want to renounce who I was before arriving to that new place. This is very important for a first generation of immigrants.

You do not have to renounce who you are to be grateful for the welcome and the invitation to be part of a new country. What makes me different is what makes me a better immigrant.

In order for that “integration” to be a real and a natural process time has to pass, maybe 3, 7, 12, 19 years, it depends from person to person, what is important is not how long it takes but how real and committed the person is to it. That is a process impossible to measure in bureaucratic terms. One has to have faith in the immigrants, one has to have trust in the society we are building together.

Integration is not about learning a language, but about understanding the differences between where you were before and where you are now.

Integration is not a one-way monologue, one has to repeat as a trained animal, it is a conversation between two cultures.

Integration is not being afraid to enrich our culture from other cultures.

Integration is not only appreciating the exotic food and the music, it is also giving people a chance to contribute with their experiences in the areas of civil society.

Integration is giving immigrants the same civil rights we fought for and we have for ourselves.

Integration is integrating immigrants into the political life.Immigration is a question of tolerance, from both sides, if we are not willing to have it then we do not have the right to claim, we don not have the right to declare, that one has entered and that one belongs to the 21st Century because if you do not understand immigrants as human beings with the same rights you belong to the older times of slavery.

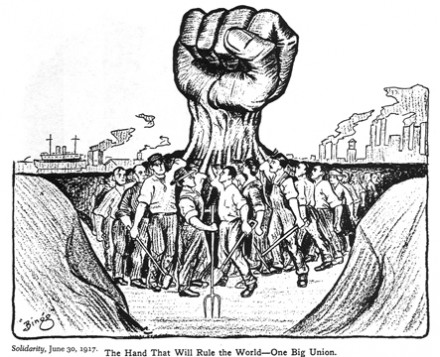

And I’m here today because I know some Germans and I have received their kindness, their smartness, their great culture, I’m here because I know that it is just a matter of time for Germany, who is known as the economic engine of Europe, to become known also as part of the engine for immigration justice. I know that people in Germany, immigrants and citizens can unite to create the first steps for this leadership.

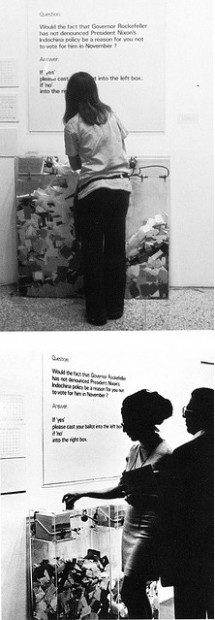

I want to propose to all of you, immigrants and citizens to create a new political party, a party for international citizens, for the citizen of the future, a political party for the rights of immigrants to be fully part of society, a political party for the right to be judged by your actions and not by what people ignore about you, a political party for the rights of immigrants to be an equal partner in the construction of a better society.

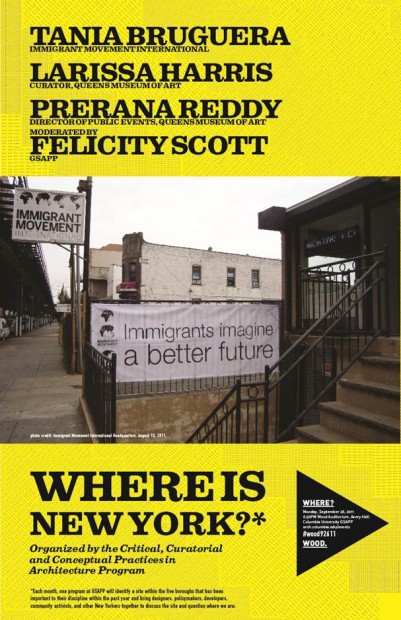

Let’s create here in Europe, in Germany, in Frankfurt, today, the political party for immigrants: Immigrant Movement International.

Let’s stand up, let’s look at people’s eyes in a few years, look at history in the face and say: we did it, we stand against injustice, this is the way to lead, this is the way to start the global immigrant era to which all of us belong, because we are all immigrants at some point.

I have heard the voice of the people here, the people who tore down the wall that divided a country before, are the people who will tear down the invisible wall that is dividing people in the world now: the wall around immigrants.

Because with immigrants we can think a better future!

Frankfurt, August 13th, 2011